Just 10 fishing vessels responsible for a quarter of harmful suspected bottom trawling in UK offshore protected areas

Press Release Date: March 20, 2024

Location:

Contact:

Daisy Brickhill | email: dbrickhill@oceana.org

New analysis reveals that the UK’s vulnerable marine habitats were subjected to over 33,000 hours of suspected bottom trawling* in 2023

- Fishing vessels equipped with bottom-towed gear were active in the UK’s offshore marine protected areas for over 33,000 hours – adding up to nearly four years – in 2023 alone.

- Just 10 vessels were responsible for over a quarter of this damaging activity – none of which were UK vessels.

- Oceana UK calls for urgent political action to achieve a complete ban on bottom trawling across all marine protected areas (MPAs), in their entirety.

© Shutterstock. Bottom trawl gear is highly destructive and can weigh several tonnes, effectively bulldozing the sea bed

The UK’s marine ‘protected’ areas were subjected to over 33,000 hours of suspected bottom trawling in 2023, reveals new analysis from Oceana UK. This destructive form of fishing effectively bulldozes seafloor habitats and has an extremely high rate of bycatch – indiscriminately scooping up untargeted wildlife. Despite this, it is permitted in almost all UK MPAs.

New analysis of satellite data from Global Fishing Watch shows that over 100,000 hours of apparent industrial fishing took place within the UK’s offshore marine protected areas in 2023 – of which 33,000 hours were from vessels carrying destructive bottom-towed gear, such as bottom trawls and dredges.

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are designated to protect rare, threatened or important ocean habitats and species to ensure healthy marine environments.

Yet these latest data indicate that industrial bottom-trawl vessels continue to drag heavy metal gear and nets – which can be as large as a football field and weigh several tonnes – across the seafloor in supposed marine sanctuaries.

10 fishing vessels account for a quarter of this destructive activity

Just 10 fishing vessels – all at least 20 metres in length – were responsible for over a quarter (27%) of the suspected bottom trawling identified by the analysis, demonstrating the intense nature of this damaging practice. None of these 10 vessels were from the UK, and just 6% of the total 33,000-plus hours of suspected bottom trawling in these MPAs was carried out by UK vessels.

Hugo Tagholm, Executive Director of Oceana UK, said: “Our marine ‘protected’ areas are crisscrossed with the scars of this highly destructive form of fishing, which may take decades to heal. These areas are vital havens for ocean wildlife and protect us against the climate crisis. Everything from sharks to starfish are hoovered up by bottom trawling, which can destroy whole ecosystems and empty our seas of life. This also threatens communities seeking to make a sustainable living from our seas. The government must act now to ban this destructive practice from all our marine protected areas. Anything less is a complete betrayal of our ocean wildlife, which urgently need sanctuaries that are safe from this wholesale destruction.”

Martin Attrill, Professor of Marine Ecology at Plymouth University: “Over a century of industrial bottom trawling and dredging has degraded the UK seabed and still threatens some of our remaining most important and sensitive marine habitats, impacting further the biodiversity and resilience of our seas. It is therefore frankly astounding that these harmful practices are still permitted in marine protected areas, designated to protect the seabed and allow nature to recover. When this particular destructive pressure is removed, our research in places like Lyme Bay shows that these marine ecosystems can bounce back, bringing wide ranging benefits. As seabed species and habitats recover, they can build up ‘blue’ carbon that helps to mitigate the climate crisis, they boost marine biodiversity and the abundance of commercial species inside and outside MPAs, with benefits to the UK fishing industry and other marine sectors, and by giving some space to nature they help restore the overall health of our seas.”

Biodiversity hotspots at risk

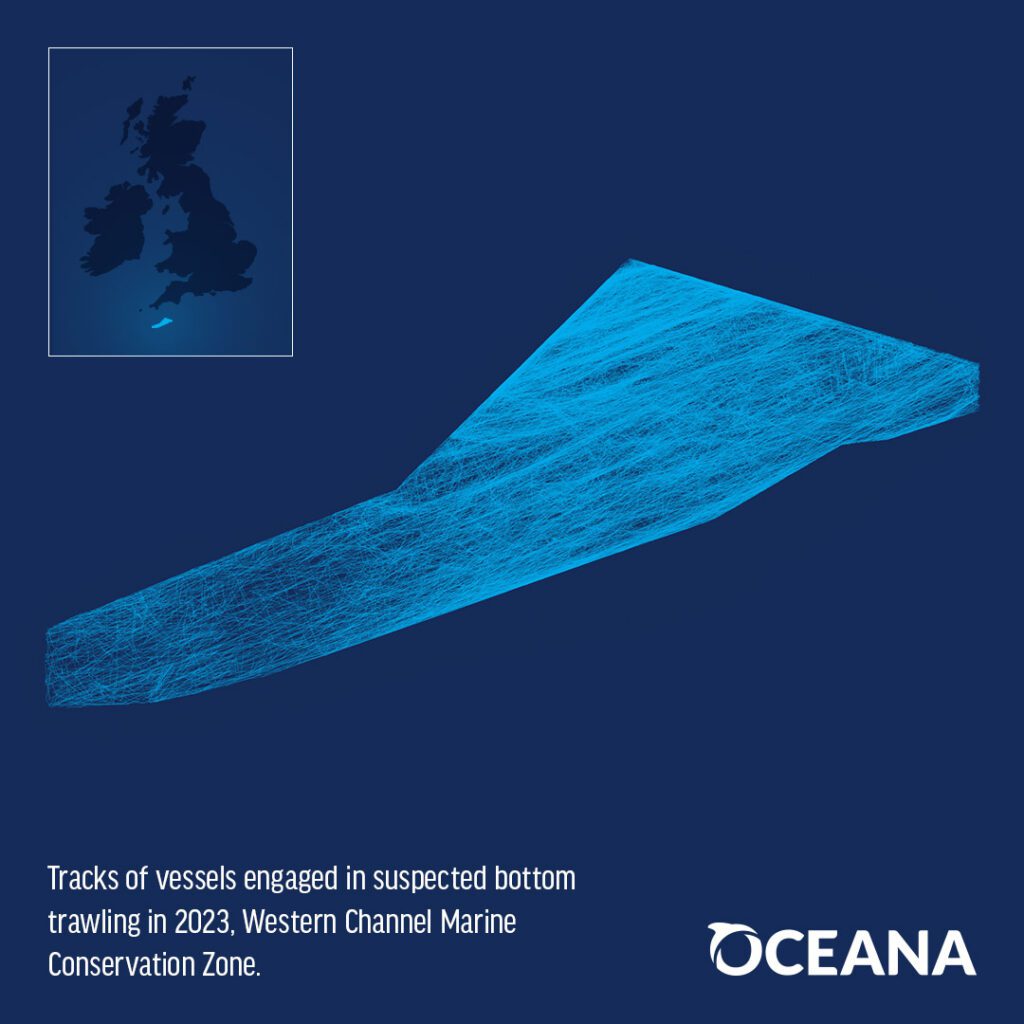

The two most exploited sites were both located off the coast of Cornwall. The Western Channel MPA is made up of underwater sand dunes that are home to wildlife ranging from the small-spotted cat shark to the angler fish. It performs a vital role by bringing nutrients from cooler, deeper waters to the surface, stimulating food chains that support an abundance of ocean life.

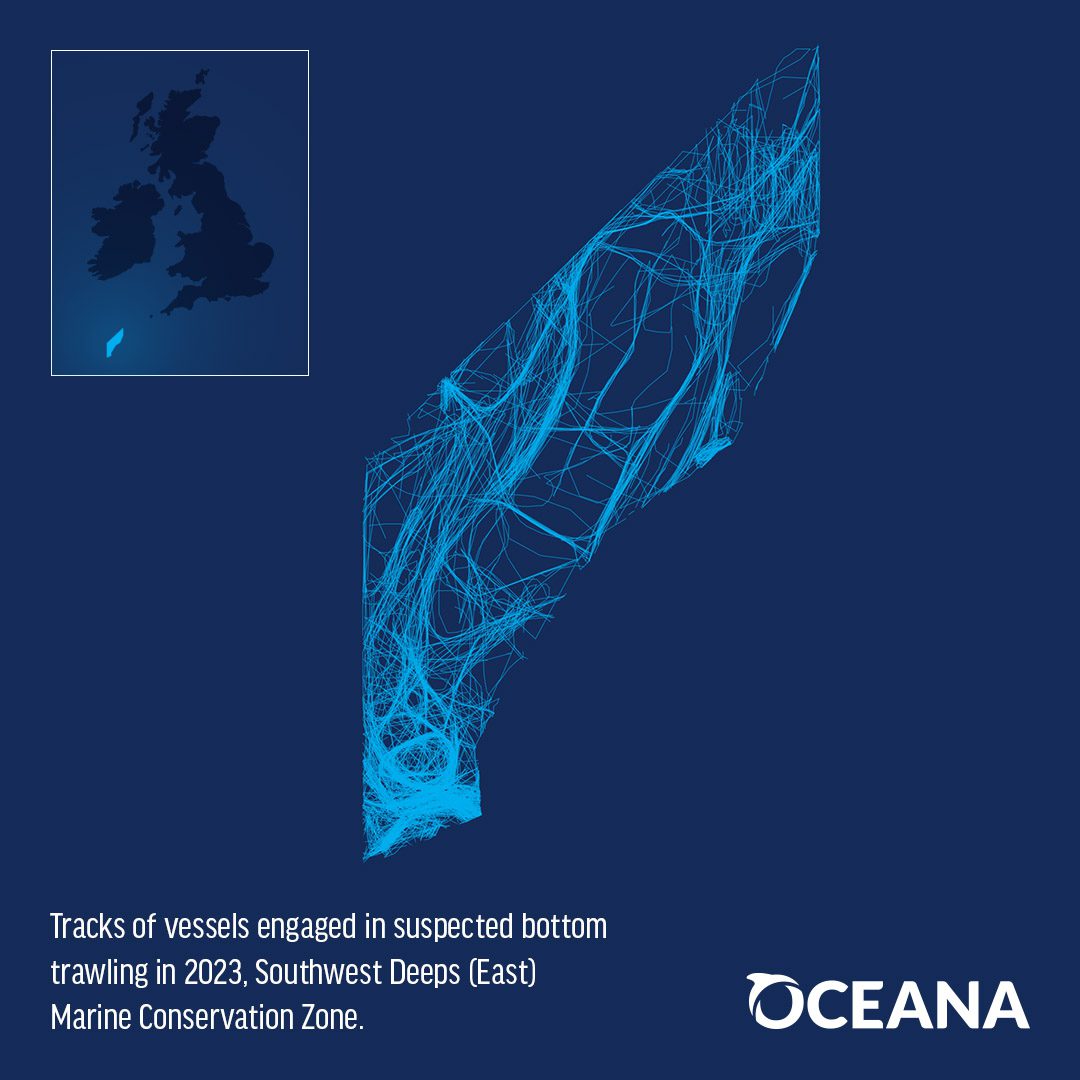

The Southwest Deeps (East) is also a crucial biodiversity hotspot, boasting cuckoo rays as well as the fan mussel, one of Britain’s largest and most threatened molluscs. This site also stores an estimated 1.67 megatonnes of carbon, which is equivalent to carbon emissions from over 1 million return flights from London to Sydney.

Urgent political action

Ahead of the UK general election, Oceana UK is calling for decisive political action on destructive fishing, urging all political parties to commit to a complete ban on bottom trawling across all marine protected areas. Polling has shown that more than three quarters of the UK public support such a ban, and Oceana is asking the public to write to the Fisheries Minister to express their concern, and support for proper protection.

The UK Government is set to begin a consultation on proposed measures for the majority of England’s remaining offshore MPAs this spring; during which Oceana will continue to push for stronger measures that protect MPAs in their entirety. The Scottish Government has also committed to delivering management measures in 2024 but has not yet presented proposed measures for consultation.

In line with legal pressure from Oceana in 2021, the UK Government has committed to restricting bottom trawling in the UK’s offshore MPAs, and has been introducing byelaws to protect certain features – such as reefs – within MPAs on a site-by-site basis, with the latest of these due to come into force on 22 March 2024.

The introduction of these byelaws is an important step, but this limited restriction still leaves the vast majority of the UK’s protected areas open to this harmful practice.

ENDS

NOTES TO EDITORS

About the data

This analysis focused on the UK’s 63 offshore benthic MPAs. These sites are located beyond 12 nautical miles from our coast, designated specifically for the importance of their seabed features.

*For this analysis, Oceana’s Illegal Fishing and Transparency team used data from Global Fishing Watch, an independent non-profit founded by Oceana in partnership with Google and SkyTruth. Oceana identified satellite tracks within MPAs that indicated industrial fishing (based on Global Fishing Watch (GFW) algorithms, machine learning, and a random manual inspection of the data by the Oceana analyst team) and then narrowed the dataset down to vessels that were registered as carrying bottom trawl or dredging gear as at least one of their gear types. This matching process is external to GFW, since the information from GFW does not currently distinguish between “bottom” and “mid-water” trawlers.

GFW uses data about a vessel’s identity, type, location, speed, direction and more that is broadcast using the Automatic Identification System (AIS) and collected via satellites and terrestrial receivers. GFW analyses AIS data collected from vessels that our research has identified as known or possible commercial fishing vessels, and applies a fishing presence algorithm to determine “apparent fishing activity” based on changes in vessel speed and direction. The algorithm classifies each AIS broadcast data point for these vessels as either apparently fishing or not fishing and shows the former on the GFW fishing activity heat map. AIS data as broadcast may vary in completeness, accuracy and quality. Also, data collection by satellite or terrestrial receivers may introduce errors through missing or inaccurate data.

GFW’s fishing presence algorithm is a best effort to mathematically identify “apparent fishing activity.” As a result, it is possible that some fishing activity is not identified as such by GFW; conversely, GFW may show apparent fishing activity where fishing is not actually taking place. For these reasons, GFW qualifies designations of vessel fishing activity, including synonyms of the term “fishing activity,” such as “fishing” or “fishing effort,” as “apparent,” rather than certain.

Any/all GFW information about “apparent fishing activity” should be considered an estimate and must be relied upon solely at your own risk. GFW is taking steps to make sure fishing activity designations are as accurate as possible. GFW fishing presence algorithms are developed and tested using actual fishing event data collected by observers, combined with expert analysis of vessel movement data resulting in the manual classification of thousands of known fishing events. GFW also collaborates extensively with academic researchers through our research program to share fishing activity classification data and automated classification techniques.

About Oceana UK – uk.oceana.org

Oceana in the UK is dedicated to ensuring UK seas get the protection they deserve. We use science-based campaigns, legal challenges and razor-sharp advocacy alongside creative storytelling to achieve measurable progress towards diverse and healthy UK waters, with ocean wildlife thriving alongside communities.

About Global Fishing Watch – globalfishingwatch.org

Global Fishing Watch, a provider of open data for use in this report, is an international nonprofit organisation dedicated to advancing ocean governance through increased transparency of human activity at sea.

The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors, which are not connected with or sponsored, endorsed, or granted official status by Global Fishing Watch.

By creating and publicly sharing map visualisations, data, and analysis tools, Global Fishing Watch aims to enable scientific research and transform the way our ocean is managed. Global Fishing Watch’s public data was used in the production of this publication.